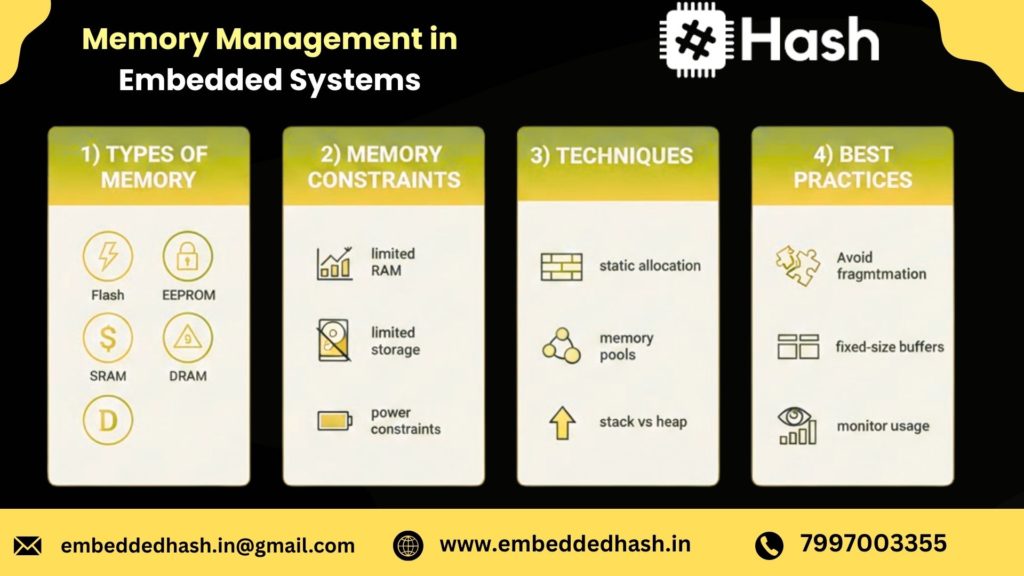

Memory Management in Embedded Systems

In modern embedded systems—whether powering automotive ECUs, consumer IoT devices, or industrial controllers—efficient memory management is the backbone of system performance and reliability. Unlike general-purpose computers, embedded devices operate within strict memory constraints, often balancing limited RAM, fixed storage, low power budgets, and real-time execution requirements. That’s why understanding how memory is allocated, optimized, and protected is crucial for building stable and scalable embedded applications

Introduction — Memory Management in Embedded Systems

Memory management is one of the most fundamental pillars of embedded system design. Unlike desktops or mobile devices, embedded hardware is built with tight memory budgets, fixed storage sizes, and strict real-time requirements. This means even a small inefficiency—an unoptimized buffer, a memory leak, or a poorly designed allocation strategy—can lead to major system failures. In embedded development, every byte counts.

Why Embedded Devices Have Strict Memory Limits

Embedded systems often run on low-cost microcontrollers with limited SRAM (2 KB–512 KB) and fixed Flash storage. These restrictions come from:

- Cost-sensitive hardware design

- Power consumption constraints

- Physical board size limitations

- Real-time processing requirements

- Application-specific architecture (e.g., automotive, IoT, industrial)

Because of these limits, developers must design memory usage deliberately, ensuring code, data, buffers, and I/O operations fit comfortably within the available space.

How Poor Memory Handling Causes System Crashes

When memory is not managed properly, embedded devices exhibit issues such as:

- Stack overflows (causing unexpected resets)

- Heap fragmentation (leading to allocation failures)

- Memory leaks (slow performance, eventual freeze)

- Corrupted pointers (undefined behavior, unsafe states)

- Flash wear-out due to inefficient write cycles

In mission-critical systems—like automotive ECUs or medical equipment—these failures can cause system downtime, safety risks, or product recalls.

What Readers Will Learn in This Guide

This guide is designed to give you a complete understanding of memory management from fundamentals to debugging. By the end, you’ll know how to:

- Understand memory types and how they work

- Design an efficient memory architecture

- Apply modern optimization techniques

- Debug memory-related issues effectively

- Implement best practices used in real-world embedded products

Concepts Covered

We’ll break down the core concepts that every embedded engineer must master:

- Static vs dynamic memory

- Flash, EEPROM, SRAM, and DRAM differences

- Memory layout (stack, heap, data, BSS)

- Interrupt-driven memory behavior

- Memory protection mechanisms

Architecture Overview

You’ll learn how embedded memory architecture is structured, including:

- How compilers allocate memory

- Linker script mapping and section placement

- Using MPUs for memory protection

- Understanding Harvard vs Von Neumann architecture

- Bootloader + application memory partitioning

Optimization Techniques

We’ll explore practical methods to reduce memory usage:

- Code size reduction (inline control, dead code removal)

- Stack usage profiling

- Heap elimination for deterministic behavior

- Flash wear-leveling

- DMA-based data movement to reduce buffer load

Debugging Strategies

You’ll get hands-on insights into debugging tools and methods:

- Detecting leaks using static analysis

- Monitoring stack usage with high-water marks

- Using JTAG/SWD for memory tracing

- Testing memory under load and long-run conditions

Real Examples

Finally, you’ll see real-world scenarios from:

- Automotive ECUs handling real-time sensor data

- IoT devices managing OTA updates on limited Flash

- Industrial systems with strict memory protection requirements

Consumer gadgets optimizing battery + memory for longer life

What Is Memory Management in Embedded Systems?

Memory management in embedded systems refers to how a microcontroller stores, organizes, and uses data and program instructions within its limited memory.

It ensures that the right data is stored in the right place, memory is not wasted, and the application runs smoothly without crashes, overflows, or delays.

In simple words:

It’s the technique of using the microcontroller’s small memory carefully so the system works efficiently and reliably.

How Microcontroller Memory Works

Every microcontroller has two major types of memory:

- Program Memory (Flash/ROM)

- Stores the firmware or code permanently

- Remains even when power is off

- Holds instructions, constant data, bootloader, etc.

- Stores the firmware or code permanently

- Data Memory (SRAM/DRAM)

- Stores temporary variables and runtime data

- Gets cleared when the device resets

- Used by the stack, heap, and global variables

- Stores temporary variables and runtime data

Internally, the MCU divides memory into regions, such as:

- Text/Code section – where machine code is stored

- Data & BSS – global & static variables

- Heap – dynamic allocation (malloc, new)

- Stack – function calls, local variables

Understanding these regions helps avoid common issues like stack overflow, fragmentation, or memory leaks.

l-World Example (ESP32 / STM32)Rea

ESP32

- Has external and internal RAM segments

- Uses Flash to store firmware

- Allocates memory for Wi-Fi/BT stack, tasks, buffers

- Requires careful splitting for FreeRTOS tasks to avoid crashes

Example:

If you run multiple Wi-Fi and BLE tasks together, poor memory allocation can cause “Guru Meditation Error” due to stack exhaustion.

STM32

- Uses tightly coupled SRAM banks

- Flash stores all program instructions

- Developers optimize memory using linker scripts (LD files)

- Ideal for real-time applications due to deterministic memory layout

Example:

Placing time-critical code in CCM (Core-Coupled Memory) improves speed because it bypasses the bus and cache.

Memory Placement Inside MCU (Short Visual Explanation)

Below is a simple text-based visual to help beginners understand where memory lives inside a microcontroller:

| Peripheral Registers (I/O) |

| Special Function RAM |

Or a more MCU-like visual:

[CPU Core]

|– Flash (Firmware)

|– SRAM Bank 1 (Stack)

|– SRAM Bank 2 (Heap / Data)

|– Registers & Peripherals

This layout helps developers understand how variables, buffers, and functions live inside the chip.

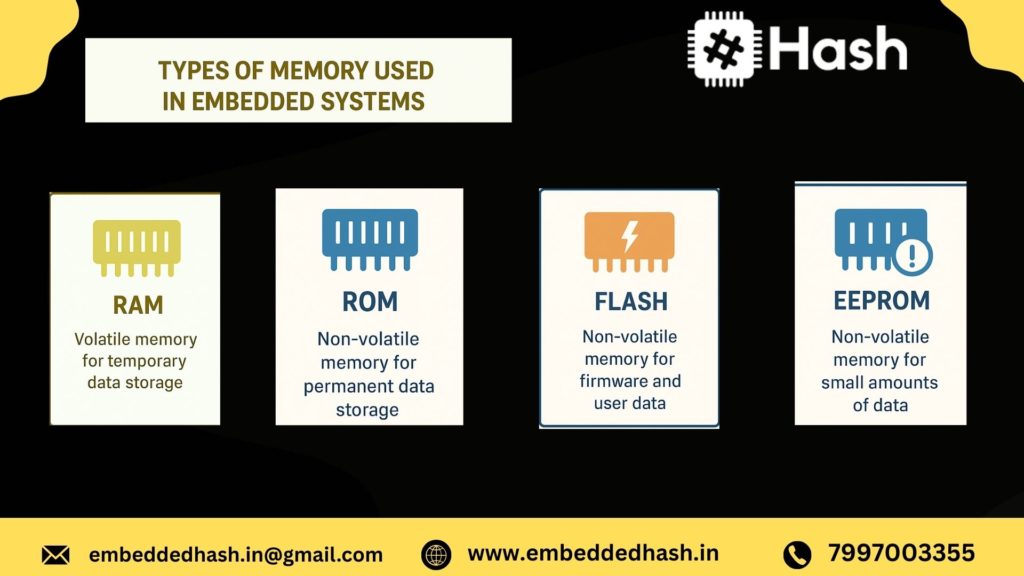

Types of Memory Used in Embedded Systems

Embedded systems use a combination of volatile and non-volatile memory to store code, variables, configuration data, and real-time processing information. Each memory type has a specific purpose based on speed, size, cost, and power consumption. Understanding these memory categories is crucial to designing reliable embedded products.

RAM (SRAM, DRAM)

RAM (Random Access Memory) is volatile, meaning it loses data when power is removed. It stores variables, runtime data, and stack/heap during program execution.

SRAM (Static RAM)

- Fastest RAM type used in microcontrollers

- Stores data using flip-flops (no refresh needed)

- Consumes more power and is expensive

- Typically used for register files, caches, and on-chip memory

DRAM (Dynamic RAM)

- Requires refresh cycles to maintain data

- Cheaper and available in larger sizes

- Used in high-performance embedded systems (Linux boards, AI edge devices)

What it stores:

- Global variables

- Local variables

- Stack/heap

- Real-time buffers

- Temporary data

Flash / ROM

Flash memory (a type of non-volatile ROM) permanently stores program code and essential system data.

Why Flash is important:

- Retains data even without power

- Supports in-field firmware updates (OTA)

- Used in all modern microcontrollers

What Flash/ROM stores:

- Main program code (firmware)

- Bootloader

- Lookup tables

- Constant variables (const data)

- RTOS kernel

- Interrupt vectors (in many architectures)

Example:

An STM32 microcontroller stores its firmware and bootloader entirely in internal Flash memory.

EEPROM

EEPROM (Electrically Erasable Programmable ROM) is a non-volatile memory used to store small amounts of data that must persist after power-off.

Key Features

- Byte-wise erase/write capability

- Limited write cycles (typically 100,000–1,000,000)

- Slower than Flash but flexible for small updates

What EEPROM stores:

- Calibration values

- User settings

- Serial numbers

- Device configuration

- Last known device state

Example:

Home appliances store user preferences (like fan speed) in EEPROM.

Cache Memory

Cache memory is a small, ultra-fast memory used in advanced MCUs/MPUs to speed up access to Flash or RAM.

Why is cache used:

- Flash and DRAM are slower than CPU speed

- Cache reduces instruction stalls

- Improves real-time performance in Cortex-A and high-end Cortex-M processors

Types of cache:

- Instruction Cache

- Data Cache

- Unified Cache

Example:

Cortex-A53 processors in Raspberry Pi use L1 and L2 cache to accelerate Linux applications

Registers are the fastest, smallest memory location inside the CPU.

Special function registers (SFRs) control timers, ADC, GPIO, UART, PWM, etc.

Purpose:

- Temporarily hold instructions/data being processed

- Control peripheral behavior

- Maintain CPU state

Examples of Registers:

- Program Counter (PC)

- Stack Pointer (SP)

- Status Register

- Timer/ADC configuration registers

Example:

Changing the PWM duty cycle in an Arduino involves writing to a Timer Control Register.

Difference Between Each Memory Type

|

Memory Type |

Volatile? |

Speed |

Typical Size |

Stores What? |

Example Use |

|

SRAM |

Yes |

Very Fast |

KBs to Few MBs |

Variables, stack, buffers |

MCU internal RAM |

|

DRAM |

Yes |

Fast |

MBs |

OS runtime data |

Embedded Linux boards |

|

Flash / ROM |

No |

Medium |

KBs to MBs |

Code, bootloader |

Firmware storage |

|

EEPROM |

No |

Slow |

Bytes to KBs |

Settings, calibration |

Storing configuration |

|

Cache |

Yes |

Ultra Fast |

Few KBs |

Temporary CPU data |

Cortex-A processors |

|

Registers/SFRs |

Yes |

Fastest |

Bytes |

CPU instructions, peripheral control |

Timer, ADC config |

Which Memory Stores Code, Variables, Bootloader, etc.?

|

Component |

Stored In |

|

Firmware / Program Code |

Flash / ROM |

|

Bootloader |

Flash (usually protected region) |

|

Global & Local Variables |

SRAM / DRAM |

|

Stack & Heap |

SRAM / DRAM |

|

Constant Data (const) |

Flash |

|

User Settings |

|

|

Peripheral Configuration |

Registers / SFRs |

|

Temporary Buffers |

RAM |

Practical Examples

Example 1: Arduino Uno (ATmega328P)

- Flash (32 KB): Stores sketch (firmware)

- SRAM (2 KB): Stores variables, stack

- EEPROM (1 KB): Stores saved user data

- Registers: Control GPIO, timers, ADC

Example 2: STM32 Microcontroller

- Flash (64 KB–2 MB): Firmware + bootloader

- SRAM (8 KB–512 KB): Variables, RTOS tasks

- EEPROM (emulated in Flash): Config data

- Cache (in high-end models): Speeds code execution

Example 3: Raspberry Pi (Linux-based)

- SD Card / eMMC: OS image + file system

- DRAM (1–8 GB): Processes, applications

- Caches (L1/L2): Performance optimization

Registers: Control peripherals via memory-mapped I/O

Memory Architecture in Microcontrollers

Microcontrollers are built with a compact and well-organized memory structure that allows them to run efficiently within tight hardware limits. Unlike desktop processors, MCUs divide memory into clear sections dedicated to program instructions, constant values, runtime variables, temporary data, and dynamic allocations. Knowing how these regions work is essential for writing reliable firmware, reducing runtime errors, and achieving predictable behavior in real-time applications.

Most popular MCU families—such as ARM Cortex-M, PIC, AVR, and RISC-V—follow a similar layout that uses Flash/ROM for program storage and SRAM for variables and processing tasks. Below is a simplified breakdown of each important memory region.

Code Memory

Code memory usually resides in Flash or ROM, and this is where the microcontroller stores:

- Firmware and program logic

- Interrupt vector tables

- Constant data

- Bootloader (if present)

Since Flash is non-volatile, the contents remain intact even when the device is powered off. This makes it ideal for long-term storage and for applications that require stable behavior after resets or OTA updates.

Data Memory

Data memory refers to the SRAM, which is used for all active processing during program execution. It handles:

- Runtime variables

- Buffers

- Temporary values

- Real-time data processing

RAM is limited in embedded systems, so efficient use is critical for optimal performance.

BSS Segment

The BSS (Block Started by Symbol) section contains global and static variables that are declared but not given an initial value.

Example: Int counter; static float temp;

Features:

- These variables are automatically set to zero at startup.

- Occupy RAM but do not require storage in Flash for initialization.

- Ideal for variables that don’t need a preset value.

Data Segment

The Data segment holds global and static variables that are defined with an initial value.

Example:int limit =50;

static char mode = 2;

Characteristics:

- Initial values are saved in Flash.

- During startup, these values are copied to RAM.

- This gives fast access during execution at the cost of consuming both Flash and RAM space.

Heap

The Heap is the area used for dynamic memory allocation, created during runtime using functions like malloc() or calloc().

It is used for:

- Variable-sized buffers

- Linked lists

- Queues and dynamic data structures

Caution: In embedded systems, the Heap can cause fragmentation, unpredictable behavior, and timing issues. For critical or real-time systems, many engineers avoid using the Heap entirely.

Stack

The Stack is where the microcontroller stores:

- Function call information

- Local variables

- Return addresses

- Register states during interrupts

Characteristics:

- It grows downward in most MCU architectures.

- Very fast and predictable, making it suitable for real-time tasks.

- A stack overflow can lead to system crashes or hard faults, so sizing it correctly is essential.

What Goes Where in Embedded Applications?

Choosing the right memory region for each type of data helps improve performance, reduce RAM usage, and avoid corruption issues.

|

Data Type |

Stored In |

Why |

|

Program instructions |

Flash |

Non-volatile and stable |

|

Constant values (const) |

Flash |

Saves RAM and prevents modification |

|

Initialized global/static variables |

Data Segment (RAM) |

Needed during execution |

|

Uninitialized global/static variables |

BSS Segment (RAM) |

Zero-initialized at startup |

|

Local variables |

Stack |

Fast and auto-managed |

|

Function parameters |

Stack |

Standard calling behavior |

|

Dynamic buffers |

Heap |

Flexible size (use carefully) |

|

Lookup tables |

Flash |

Reduces RAM use |

|

ISR context and temporary data |

Stack |

Part of interrupt handling |

Tip: Place constants in Flash, minimize global variables, manage stack usage carefully, and avoid Heap in time-critical systems.

Stack vs Heap in Embedded Systems

Memory in embedded systems is often limited, tightly controlled, and critical to system stability. That’s why Stack vs Heap is one of the most searched topics in embedded engineering—especially among beginners trying to understand why embedded programs behave differently than PC applications.

In resource-constrained microcontrollers like ARM Cortex-M, AVR, or PIC, choosing between stack and heap memory is not just a programming preference; it directly impacts performance, determinism, and reliability.

What is Stack?

The stack is a predetermined memory area primarily used for:

- Local variables

- Function parameters

- Return addresses

- Temporary storage during function calls

In embedded systems, the stack is typically small (2 KB to 16 KB for many MCUs), but it is fast, predictable, and automatically managed.

Key features of Stack:

- Static allocation (compile-time known size)

- Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) mechanism

- Very fast access

- No fragmentation

- Automatically cleaned when a function exits

Because of its deterministic behavior, the stack is heavily used in real-time systems.

What is Heap?

The heap is a memory region used for dynamic allocation—memory allocated at runtime using functions like:

malloc()

calloc()

realloc()

free()

Heap memory is flexible but less predictable. It grows and shrinks at runtime, which can cause:

- Fragmentation

- Allocation failures

- Long and unpredictable allocation times

In embedded systems, heaps are usually very small, especially in MCUs with limited RAM.

Key Differences (Speed, Size, Lifetime, Fragmentation)

Feature | Stack | Heap |

Speed | Extremely fast (linear access) | Slower (managed by allocator) |

Size | Small & fixed | Larger but limited |

Lifetime | Until function exits | Until free() or system reset |

Fragmentation | No fragmentation | Highly prone to fragmentation |

Allocation Type | Static / automatic | Dynamic / runtime |

Determinism | Predictable | Not predictable |

Use Case | Real-time tasks, local variables | Large buffers, dynamic data structures |

In real-time embedded systems, determinism is king, making stack the preferred choice.

Real Embedded C Examples

Example 1: Stack Allocation (Safe & Fast)

void task_handler() { uint8_t buffer[64]; // Allocated on stack

// Use buffer…}

- Fast

- Predictable

- Released automatically when function ends

Example 2: Heap Allocation (Risky in Embedded)

void process_data() {

uint8_t *data = (uint8_t *)malloc(128);

if (data != NULL) // Access memory

Slow allocation

Risk of memory leaks

Risk of fragmentation

Stack Overflow & Heap Fragmentation Explained

1. Stack Overflow

Occurs when the stack pointer exceeds its limit, typically caused by:

- Deep or infinite recursion

- Large local arrays

- Multiple nested function calls

- RTOS tasks with small stack sizes

Result: System crash, HardFault, or unexpected MCU reset.

Example (dangerous):

void bad_function() {

uint8_t huge_array[4096]; // Too big for stack!}

2. Heap Fragmentation

Occurs when small pieces of free heap memory are scattered between allocated blocks.

Symptoms:

- malloc() returns NULL even if total free memory is sufficient

- Memory becomes unusable over time

- Device behaves erratically after long runtime

Fragmentation is especially dangerous for long-running IoT devices.

Why Most Embedded Engineers Avoid Dynamic Allocation

Most embedded engineers avoid malloc()/free() because:

- Non-deterministic allocation time (bad for real-time systems)

- Heap fragmentation risk

- Hard to debug memory leaks

- Limited RAM in microcontrollers

- Potential system crashes

Best Practices (2026 Standards)

- Prefer static or stack allocation

- Use RTOS memory pools instead of malloc

- Allocate once at startup if dynamic allocation is needed

- Avoid dynamic memory in ISR (Interrupts)

- Enable MPU (Memory Protection Unit) for runtime protection

Static vs Dynamic Memory Allocation (With Embedded C Examples)

Memory allocation is a critical design decision in embedded systems. Choosing between static and dynamic memory directly impacts reliability, timing, performance, and long-term stability—especially in real-time and safety-critical applications like automotive ECUs, medical devices, and IoT controllers.

Static Memory Allocation: Benefits

Static memory allocation means memory is assigned at compile time, not during program execution. This is the preferred method in most embedded designs because it provides predictability, which is essential for real-time behavior.

Key advantages:

- Deterministic execution

No runtime delays—memory is already reserved before the program starts. - No fragmentation issues

Unlike dynamic allocation, static memory stays fixed in size and location. - Safer for low-power MCUs

Ideal for systems with limited RAM (e.g., Cortex-M0/M3 boards, AVR, PIC). - Easy debugging & testing

Memory layout is predictable, improving code reliability.

Embedded C Example – Static Allocation

// Static allocation of array and struct in embedded C

static uint8_t sensorBuffer[64];

typedef struct { uint16_t temperature; uint16_t humidity;}

SensorData; static SensorData envData;

This ensures the memory footprint is known at compile time—a critical requirement in many embedded systems.

When Dynamic Memory Is Dangerous (Especially in Real-Time Systems)

Dynamic memory (malloc, calloc, realloc, free) is common in desktop applications—but risky in embedded environments, particularly in real-time systems.

Why it becomes dangerous:

- Unpredictable allocation time

You can’t guarantee how long malloc() will take, breaking real-time deadlines. - Possible memory leaks

If memory is allocated but never freed (or freed incorrectly), your MCU will eventually crash. - No built-in garbage collection

Unlike high-level platforms, embedded C puts full responsibility on the programmer. - Limited heap size

Low-cost MCUs may only have a few KB of heap, making fragmentation catastrophic.

Embedded C Example – Risky Dynamic Allocation

uint8_t *buffer = (uint8_t*) malloc(128);

if(buffer == NULL) { // System may fail due to insufficient heap}

Even this simple call may cause unpredictable delays or failures in a time-critical system.

Memory Fragmentation Issues

One of the biggest long-term problems with dynamic memory allocation in embedded systems is fragmentation.

Types of fragmentation:

- External fragmentation

Free memory exists, but in small scattered blocks—not enough for a large allocation. - Internal fragmentation

Allocator gives more memory than requested, wasting RAM.

This leads to:

- Random system crashes after long uptime

- Increased RAM consumption over hours/days

- Failure of mission-critical tasks

- Inconsistent behavior in RTOS-based systems (FreeRTOS, Zephyr, ThreadX)

If your embedded device needs to run 24/7—like smart meters, routers, medical monitors, drones, industrial gateways—fragmentation can silently break your system.

Example of fragmentation scenario:

void example() {uint8_t *a = malloc(20);

uint8_t *b = malloc(30);

free(a); uint8_t *c = malloc(25); // May fail due to fragmented blocks}

Even with enough total free memory, allocation may fail due to scattered blocks.

Common Memory Challenges in Embedded Systems

Embedded systems, due to their resource-constrained nature, face unique memory challenges that can affect performance, reliability, and safety. Understanding these pitfalls is crucial for robust embedded software design.

Memory Leaks

Memory leaks occur when dynamically allocated memory is not freed properly, gradually consuming RAM and potentially crashing the system.

Example: In an IoT sensor node, repeatedly allocating memory for sensor data without freeing old buffers can lead to system lock-up over days.

Prevention:

- Use static memory allocation where possible.

- Implement memory tracking mechanisms.

- Periodically audit heap usage with debugging tools like Valgrind or RTOS-specific monitors.

Buffer Overflow

Buffer overflows happen when data exceeds allocated memory, potentially overwriting adjacent memory and causing erratic behavior or security vulnerabilities.

Example: Writing 32 bytes into a 16-byte array for UART data can corrupt nearby stack variables.

Prevention:

- Always check array bounds.

- Use secure string handling functions (for example, strncpy rather than strcpy).

- Enable compiler warnings for unsafe memory operations.

Stack Overflow

Stack overflow occurs when recursive calls or deep function nesting consume more stack than allocated. This can crash the microcontroller or lead to unpredictable behavior.

Example: Excessive recursion in a sensor processing algorithm on STM32.

Prevention:

- Analyze maximum call depth.

- Reduce recursion; use iterative solutions.

- Increase stack size in RTOS configurations when necessary.

Memory Fragmentation

Frequent dynamic allocation/deallocation can fragment memory, leaving small unusable blocks scattered across the heap.

Example: In ESP32, allocating and freeing Wi-Fi buffers repeatedly may lead to heap exhaustion.

Prevention:

- Use memory pools for frequently allocated objects.

- Prefer static memory allocation.

- Monitor heap fragmentation via embedded memory analyzers.

Pointer-Related Errors

Dangling or null pointers can lead to segmentation faults or data corruption.

Example: Dereferencing a pointer after freeing memory in Arduino UNO code.

Prevention:

- Initialize pointers to NULL.

- Set pointers to NULL after freeing memory.

Use static analysis tools to catch pointer misuse.

How to Optimize Memory in Embedded Systems

Efficient memory use is critical for embedded systems, especially with AI workloads, OTA updates, and mixed-memory architectures in 2026 devices. These strategies help developers optimize RAM and Flash usage.

Use Appropriate Data Types (uint8_t vs int)

Smaller data types reduce memory footprint. Example: Use uint8_t for counters instead of int when the range allows.

Reduce Global/Static Variable Usage

Excessive global/static variables occupy RAM throughout program execution.

Tip: Prefer local variables or dynamic allocation within controlled bounds.

Memory Pooling

Pre-allocate fixed-size memory blocks to reduce fragmentation and speed up allocation/deallocation.

Use const and static Efficiently

- const for read-only data stored in Flash instead of RAM.

- static for internal function variables reduces external memory access.

Enable Compiler Optimization Flags (O1, O2, Os)

Modern compilers optimize memory and code size; -Os reduces binary size for RAM-limited systems.

Reduce Function Call Depth (Stack Saving)

Flatten function hierarchies to avoid stack overflows, particularly in recursive algorithms.

Replace Heavy Code with Lookup Tables

Precompute results for frequently used computations to save CPU cycles and stack usage.

Example: Trigonometric functions replaced with precomputed sine/cosine tables in STM32 projects.

Minimize String Usage

Avoid dynamic strings; use fixed-length buffers. Store constants in Flash to save RAM.

Memory Debugging Tools for Embedded Systems

Modern embedded development requires proactive memory debugging. The following tools are essential in 2026 embedded systems engineering.

Valgrind (Simulated Testing)

Detects memory leaks, uninitialized memory, and invalid accesses in simulated environments before deployment.

JTAG / SWD Debugging Tools

Provides live memory inspection, breakpoints, and real-time stack monitoring on microcontrollers like STM32 and ESP32.

Keil / IAR Memory Analyzer

Tracks memory allocation, stack usage, and fragmentation for ARM Cortex-M devices. Helps optimize embedded RTOS applications.

ESP-IDF Memory Analyzer

ESP32-specific tool for heap monitoring, memory fragmentation analysis, and leak detection in FreeRTOS environments.

Static Analysis Tools

Tools like PC-lint, Coverity, or Cppcheck identify potential memory errors at compile time, reducing runtime issues.

Real Board Examples: Memory Usage & Optimization

STM32

- Memory Map: SRAM 20–512 KB, Flash 64 KB–2 MB

- Limitations: Stack and heap share SRAM; careful allocation required

- Optimization: Use DMA buffers in Flash, reduce global variables

ESP32

- Memory Map: 520 KB SRAM, external PSRAM optional

- Limitations: Heap fragmentation with Wi-Fi + BLE + RTOS tasks

- Optimization: Memory pooling, allocate critical buffers in internal SRAM

Arduino UNO

- Memory Map: 2 KB SRAM, 32 KB Flash

- Limitations: Extremely constrained RAM

- Optimization: Store constants in PROGMEM, minimize dynamic allocation

Raspberry Pi Pico (RP2040)

- Memory Map: 264 KB SRAM, 2 MB Flash

- Limitations: Split SRAM banks; stack placement critical

- Optimization: Use scratchpad memory and reduce recursion depth

Practical Tips:

- Always analyze memory usage per task in RTOS systems

- Map stack and heap regions to avoid overlaps

Use static allocation for time-critical or frequently used buffers

Conclusion — Memory Management in Embedded Systems

Memory management in embedded systems is not just a technical requirement—it’s a cornerstone for building robust, real-time, and energy-efficient applications. By mastering memory allocation strategies, understanding the nuances of different memory types, and implementing best practices like dynamic memory handling, buffer management, and memory protection, engineers can design systems that are reliable, scalable, and secure.

Whether you are developing IoT devices, automotive controllers, or industrial embedded solutions, a deep understanding of memory management ensures your system performs optimally under strict constraints. Investing time in efficient memory usage today translates into reduced system failures, lower costs, and enhanced user satisfaction tomorrow.

Stay ahead in the embedded world by treating memory management as a strategic priority, not just an afterthought, and build systems that are fast, safe, and future-ready.

Memory management in embedded systems is not just a technical requirement—it’s a cornerstone for building robust, real-time, and energy-efficient applications. By mastering memory allocation strategies, understanding the nuances of different memory types, and implementing best practices like dynamic memory handling, buffer management, and memory protection, engineers can design systems that are reliable, scalable, and secure.

Whether you are developing IoT devices, automotive controllers, or industrial embedded solutions, a deep understanding of memory management ensures your system performs optimally under strict constraints. Investing time in efficient memory usage today translates into reduced system failures, lower costs, and enhanced user satisfaction tomorrow.

Stay ahead in the embedded world by treating memory management as a strategic priority, not just an afterthought, and build systems that are fast, safe, and future-ready.

Frequently Asked Questions

Memory management in embedded systems is the process of efficiently allocating, using, and freeing memory in devices with limited resources. It ensures smooth program execution, prevents crashes, and optimizes performance for real-time applications. Proper memory management balances RAM, ROM, Flash, and sometimes cache, depending on the embedded hardware.

The stack is preferred because it provides fast, deterministic memory allocation with minimal overhead. Stack memory is automatically managed, reducing fragmentation risks. In contrast, heap allocation is dynamic, slower, and can lead to fragmentation and unpredictable execution times—critical issues in real-time embedded systems.

Memory fragmentation occurs when free memory blocks are scattered in non-contiguous spaces. In embedded systems, frequent dynamic allocation and deallocation on the heap lead to fragmentation, making it difficult to allocate large continuous memory blocks, which can cause system instability.

Microcontrollers typically have kilobytes to a few megabytes of RAM and Flash memory. For example, entry-level 8-bit MCUs may have 2–8 KB RAM, while high-end ARM Cortex-M MCUs can have 256 KB to 1 MB of RAM and several megabytes of Flash. The exact size depends on the MCU architecture and application requirements.

Common memory errors include:

- Buffer overflows – writing beyond array bounds

- Dangling pointers – accessing freed memory

- Memory leaks – failing to free dynamically allocated memory

- Stack overflow – exceeding stack memory due to recursion or large local variables

- Uninitialized memory use – reading memory before assignment

These errors can lead to crashes, unexpected behavior, or system vulnerabilities.

You can reduce memory usage by:

- Optimizing data types (e.g., use uint8_t instead of int)

- Minimizing global/static variables

- Using lookup tables instead of computation

- Avoiding unnecessary dynamic memory allocation

- Enabling compiler optimization flags (-Os)

Using memory-efficient data structures like bitfields

- SRAM: Volatile memory used for fast read/write operations during runtime. Data is lost when power is off. Ideal for temporary storage like stack and heap.

- Flash: Non-volatile memory used to store program code and persistent data. Retains data without power but has slower write speeds and limited write cycles.

Dynamic memory allocation allows programs to request memory at runtime from the heap using functions like malloc() and calloc(). While flexible, it can cause fragmentation and unpredictable execution, so many real-time embedded systems minimize or avoid its use.

Microcontrollers have limited RAM to reduce cost, power consumption, and die size. Unlike PCs, embedded systems are designed for specific tasks rather than general-purpose computing, so memory is optimized for application requirements, not over-provisioned.

A Memory Protection Unit (MPU) is a hardware feature in many modern microcontrollers (like ARM Cortex-M) that controls how memory regions are accessed. It prevents illegal reads/writes, blocks stack overflows, and enhances security by isolating tasks. MPUs are essential for building safe, secure, and real-time embedded applications.

Flash wear-out occurs because Flash memory supports a limited number of program/erase (P/E) cycles, typically between 10,000 to 100,000 cycles depending on the MCU. Repeated writes degrade the memory cells over time. Wear-leveling, caching, and minimizing frequent writes help extend Flash lifespan.

If you want to Learn more About Embedded Systems, join us at Embedded Hash for Demo Enroll Now

embeddedhash.in@gmail.com

embeddedhash.in@gmail.com